Barefoot doctor: the special identity of village doctors in the times

Barefoot doctor: the political embodiment of village doctors

Our reporter/Li Mingzi

Published in China Newsweek, No.1019, November 8, 2021.

After practicing medicine in the countryside for 54 years, Ma Wenfang is still used to being called "barefoot doctor" by villagers, although this title has been officially cancelled since 1985.

The term "barefoot doctor" first appeared in the people’s commune period of the last century. In the summer of 1968, Red Flag, sponsored by The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CCCPC), published a survey report on the direction of medical education revolution from the growth of barefoot doctors in Shanghai. At the beginning of the article, I wrote, "Barefoot doctor" is an affectionate name for poor middle peasants in the suburbs of Shanghai who are semi-medical and semi-agricultural health workers. "

This article was published in People’s Daily on September 14th of the same year on the instruction of Mao Zedong, and "barefoot doctor" soon became a hot topic of public opinion at that time. Barefoot doctors everywhere have naturally become "typical" reported by the media-"Cowboy in the old society" studies medicine hard and treats incurable diseases for poor and middle peasants by virtue of "a red heart for great leaders". The image of barefoot doctors was painted in posters, comic books and even printed on stamps, food stamps and calendars, which became a vivid symbol of that era.

For Ma Wenfang, a village doctor in Suliuzhuang Village, Dagangli Township, Tongxu County, Henan Province, despite the aura of this group in a special era, barefoot doctors’ greatest contribution is to provide farmers with the most basic health protection. At that time, barefoot doctors walked in the fields with straw hats on their heads and medicine boxes on their backs to prevent and treat diseases for farmers who lacked medical care. When malaria was prevalent, it was also these barefoot doctors who went door-to-door to ask for advice, "delivering medicine to the hands, seeing the mouth, not swallowing and not walking", and finally eliminated malaria.

In its annual report from 1980 to 1981, the United Nations Children’s Fund concluded that China’s "barefoot doctor" model provided primary care for backward rural areas and provided a model for underdeveloped countries to improve their medical and health standards.

After the 1980s, the people’s commune system collapsed, and the barefoot doctor system established on this basis also disappeared. The book From Barefoot Doctors to Rural Doctors records that although the forms of medical services in rural areas have changed since then, the main staff of rural doctors are still barefoot doctors. Many of them have been working until today in the 21st century.

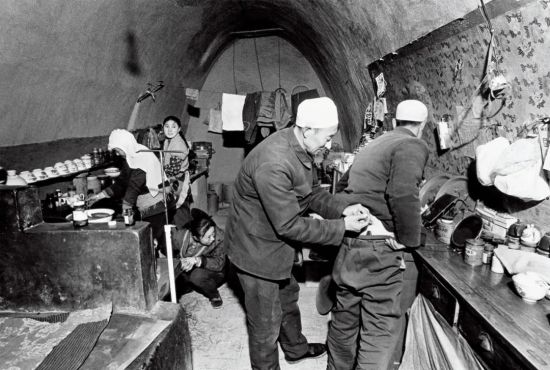

The birth of rural political stars

"In the 1950s and 1960s, there were no doctors in our village." Ma Wenfang recalled to China News Weekly that at that time, large-scale communes had hospitals, while small-scale communes didn’t even have clinics, and some small communes might have old Chinese medicine practitioners. At that time, ordinary people generally had no money to buy medicine. If farmers had a fever or a cold, they would eat a handful of millet, drink a bowl of hot water, go home to bed and sweat. If you are seriously ill, you can’t afford to go to the hospital in the city, so you can only go home and die.

Lack of doctors and medicines was a common situation at that time, and in rural areas with poor economic conditions, doctors and medicines were even more scarce. According to statistics, in 1964, 69% of senior health technicians were in cities and 31% in rural areas, of which only 10% were below the county level. At that time, the population distribution was just the opposite. The urban population only accounted for 1/10, and over 90% of the population lived in rural areas.

Ma Wenfang’s mother died of typhoid fever in the 1960s at the age of 32. Five days after his mother died, his 8-year-old brother contracted cold again. The child is skinny, because there is no doctor and no medicine, and he will be unconscious after a few days of illness. Nearby villagers donated 169 life-saving money for 1 cent and 2 cents, and then took Ma Wenfang’s brother to Kaifeng People’s Hospital for treatment. Five days later, he died.

"In less than two months, my family lost two lives. At that time, I knelt at the grave and swore that I would be a doctor, treat my fellow villagers and repay my kindness. " Ma Wenfang recalled.

At that time, the new rural health care system was being explored. In August 1950, the first national health conference was held. In view of rural health care, the idea of "setting up health centers in counties, health centers in districts, health committees in administrative villages and health workers in natural villages" was put forward. While strengthening the construction of rural grass-roots health institutions, medical personnel are also organized to go to the countryside to support rural grass-roots units.

In January, 1965, Mao Zedong approved the Report of the Party Group of the Ministry of Health to the Central Committee on Organizing Mobile Medical Teams to Go to Rural Areas. Taking this directive as a major political task, all localities quickly organized medical teams to go to rural areas, forest areas and pastoral areas to conduct roving medical treatment. Huang Jiasi, an expert in thoracic surgery, Zhou Huakang, an expert in pediatrics, and Lin Qiaozhi, an expert in gynecology, have all participated in itinerant medical treatment.

In this regard, Yang Nianqun, a professor at the Institute of Qing History of Renmin University of China, pointed out in his article "Epidemic Prevention Behavior and Spatial Politics" that for a long time after liberation, medical personnel only visited the countryside irregularly in the form of ambulance teams, and it was impossible to form a relatively institutionalized network of diagnosis, treatment and epidemic prevention in the vast rural areas.

On June 26, 1965, Mao Zedong said after listening to the work report of the Ministry of Health: "The work of the Ministry of Health only serves 15% of the national population, and the 15% is mainly the old man. The vast number of farmers have no medical treatment, no medical treatment and no medicine. The Ministry of Health is not the Ministry of Health of the people, but the Ministry of Health of the city or the Ministry of Health of the city, or the Ministry of Health of the city! " Mao Zedong instructed: "The focus of medical and health work should be placed in the countryside!" "Cultivate a large number of doctors who can afford it in rural areas, and they will serve farmers."

This passage was later called "June 26 instruction". On September 1 of the same year, People’s Daily published an editorial entitled "Putting the focus of medical and health work in rural areas" on the front page. The word "barefoot doctor" was not mentioned at that time.

Shanghai took the lead in piloting. In the summer of 1965, Jiangzhen Commune, Chuansha County, Shanghai began to run a training course. Huang Yuxiang, who graduated from Suzhou Medical College, served as a teacher, teaching medical common sense and simple treatment methods. After studying in a crash course for 4 months, the students returned to the commune as health workers. Wang Guizhen, who was later called "the first barefoot doctor in China", was one of the first students in this training class.

Wang and Huang used the method of "combining local culture with foreign culture" to save money for local villagers to see a doctor, and they also had to farm in the fields every day. The name "barefoot doctor" became popular among villagers unconsciously. In 1968, Shanghai Wen Wei Po published a report on Wang and Huang-Looking at the direction of medical education revolution from the growth of "barefoot doctors". This article was subsequently reprinted in full by Red Flag magazine and People’s Daily.

Due to the urgent demand for medical resources in rural areas and the political background of the personal instructions of the top leaders in special periods, the "barefoot doctor" system has been rapidly popularized throughout the country. According to the Report of the Ministry of Health on the National Working Conference of Barefoot Doctors at that time, by the end of 1975, the number of "barefoot doctors" in rural areas of China had reached more than 1.5 million, and there were more than 3.9 million health workers and midwives in production teams.

"Class composition" and "ideological consciousness" are the primary criteria for selecting barefoot doctors. An article by Xinhua News Agency published in the fifth edition of People’s Daily on June 23, 1969: "Students are recommended by poor lower-middle peasants and approved by the commune revolutionary committee, and the children of poor lower-middle peasants with good composition, high ideological awareness, active labor and certain culture are sent to training classes for study; The living expenses of the students are borne by the brigade. After graduation, they will return to the team to treat the poor and middle peasants. "

In 1967, Ma Wenfang, who had finished junior high school, was elected as a "barefoot doctor" by the brigade to study in the commune training class for one year. According to Ma Wenfang’s memory, at that time, it was necessary to learn anatomy, physiology and diagnostics of western medicine, but also to recite Chinese herbal medicines and learn acupuncture. Students did not have textbooks, only one-page materials printed by mimeograph.

Being a barefoot doctor is easier to earn more work points than ordinary villagers. According to Ma Wenfang’s memory, there was no salary during the people’s commune period, and they all earned work points. In Ma Wenfang’s brigade, according to the content and quantity of labor, each person can earn at most 10 points per day and at least five or six points, while being a barefoot doctor can be regarded as "full attendance", with 280 points per month, and receiving food from the production team at the end of the month.

At that time, cooperative medical care was adopted in rural areas, and the primary medical expenses were co-ordinated by the production brigade. In Ma Wenfang’s brigade, each person pays 10 cents a month, and the rest is the responsibility of the brigade. Thanks to the support of the collective economy, farmers can enjoy the most basic medical care requirements at very little cost. The article "Analysis of the reasons for the success of rural medical cooperation in the period of people’s commune" points out that "the existence of people’s commune system ensures the low-cost operation of rural cooperative medical system. Under the rural cooperative medical system, the rural health website consisting of village health stations, commune health centers and county hospitals covers almost all villages in the country. "

Yang Nianqun pointed out that it was not until the establishment of the barefoot doctor system that the instructions of the upper medical administration, such as vaccination, vaccination and distribution of anti-epidemic drugs, were really implemented, and the orders were banned, which was rapid and abnormal.

Writer Zhu Yong noticed a very interesting phenomenon. In all contemporary art works, barefoot doctors almost invariably appear as girls. In his book The Fate of Diseases in Revolution: The Saints’ Description of Barefoot Doctors, he wrote that in reality, an old image of Chinese medicine will give patients a sense of trust, but the art is different. The painter subconsciously endowed barefoot doctors with "the function of a goddess in European classical painting", and the barefoot doctors’ interpretation of life in the image of girls came not only from their careers, but also from their bodies themselves.

Barefoot doctors became the political stars of that era, not only had the opportunity to participate in the National Day parade, but also became the protagonists in political propaganda films. Wang Guizhen, a barefoot doctor, is the prototype of the leading role in the film "Spring Seedling". In addition to the real medical experience, Tian Chunmiao, the leading role of the film, is also given a "political task". Tian Chunmiao is different from the "doctor in the system" who only cares about cutting-edge topics, regardless of the life and death of poor and middle peasants. She not only cares about the proletariat, but also has a first-class medical service, which cured the waist and leg disease of poor peasant Shui Changbo, thus allowing Shui Changbo to successfully join the struggle with the director of the hospital.

Limited medical security

"Due to the limited professional medical level of barefoot doctors, the medical problems they can actually solve are limited. It can only be said that under the conditions at that time, barefoot doctors provided a kind of help to the grassroots." Zhang Daqing, director of the Department of Medical History and Philosophy in peking university health science center, analyzed China Newsweek.

Ma Wenfang also said that barefoot doctors mainly deal with common diseases such as headache, brain fever and tracheitis. If they encounter diseases that require surgery such as acute appendicitis, they need to be transferred to a higher level hospital as soon as possible. The daily work is to carry a medicine chest to work in the fields, which contains acupuncture needles, common medicines and the "old three", namely stethoscope, sphygmomanometer and thermometer. In summer, when someone gets sunstroke while working in the field, Ma Wenfang immediately goes over to relieve the heat. If someone bumps and scratches, he will go over to disinfect and bandage; When pesticides are used in cotton fields, people are often poisoned by inhaling pesticides. Later, people often commit suicide by drinking pesticides, so barefoot doctors should go to first aid.

The book Creation and Reconstruction —— Research on Rural Cooperative Medical System and Barefoot Doctors in Collectivization Period concludes that by the mid-1960s, due to continuous study, practice and training, health care workers (later barefoot doctors) had mastered the treatment of dozens of common diseases, the use of dozens of drugs, acupuncture and simple Chinese herbal medicine knowledge.

At that time, drugs were still in short supply and the price was high. Farmers only spend two cents to buy two aspirin when they have a bad cold. If they can’t cure it, they will add a penicillin. Ma Wenfang remembers very clearly that the purchase price of a penicillin is 15.8 cents and the selling price is 18 cents, which is the same price in the whole country.

"At that time, everyone earned work points, and everyone did not have the concept of making money." Ma Wenfang explained that the medicine was bought by the Murakami Brigade with money, and the income went to the public. At that time, it was a planned economy, and there was no need to buy more precious antibiotics like penicillin. Each brigade in each village received up to 10 antibiotics per month.

Zhang Daqing believes that barefoot doctors have played a positive role in the modernization and popularization of drugs in rural areas. As for the "barefoot doctors aggravated the abuse of antibiotics" mentioned in some studies, Zhang Daqing thought it was a kind of "hindsight". Antibiotics could relieve patients’ pain relatively quickly at that time, but the drug use standard was not popular at that time, so it was not appropriate to delve into it.

Under the conditions at that time, few farmers could afford western medicine, and most villagers still relied on "three soil and four self-reliance" to see a doctor, that is, native medicine, earthwork, native medicine, self-collected, self-planted, self-made and self-used Chinese herbal medicines. Ma Wenfang also specially bought a medicine mill to grind herbs into powder, or add water to make pills.

According to the report of People’s Daily on February 14th, 1969 on Li Rongyu, a barefoot doctor in Gaowang Brigade of Qibao Commune in Xinhui County, Guangdong Province, Li Rongyu’s Qibao Commune is located in the Pearl River Delta, and there are no mountains nearby, and the commune does not grow Chinese herbal medicines, so he went to the mountainous area dozens of miles away to collect herbs.

Zhang Kaining, director of the Health Research Institute of Kunming Medical College, believes that the widespread use of Chinese herbal medicines by barefoot doctors in those years consolidated the rural cooperative medical system. Chinese herbal medicine is easy to obtain, economical and cheap, and has a tradition and habit of using it in rural areas. The use of Chinese herbal medicine not only reduces the economic burden of farmers, but also greatly reduces the expenditure of cooperative medical fund.

"At that time, I was courageous, but now I can’t do it. First, the patient refused to eat (the earthwork), and another, it was illegal for doctors to do so." Ma Wenfang recalled that the appearance of barefoot doctors in those years changed the dilemma of lack of medical care and medicine in rural areas. Otherwise, people were ill and had to go home to die, so there were almost no cases of patients bothering doctors or suing doctors at that time, which was also the patient’s trust that barefoot doctors "came in the wind and went in the rain".

At that time, the dirt roads in the countryside were rugged and there were no bicycles. Going to the villagers’ homes to see doctors depended on walking. Once Ma Wenfang went out to see someone else, just in time for his wife to give birth at home. When he came back a moment later, his wife and children were gone. Since I think about it, Ma Wenfang still feels very guilty about his family.

"Barefoot doctors have a very distinctive class identity. In the screening process, they can only come from the class that is divided into’ poor and middle peasants’ by class composition. Because of his poor background, barefoot doctors are full of moral salvation, with strong love and hate and emotional tendency. Such a feeling also determines the choice of medical objects, which can only be people consistent with their class attributes. Their class attribute also determines that they will have a’ selfless’ character in the treatment process. " Yang Nianqun summed up in "Rebuilding the Patient —— Space Politics under the Conflict between Chinese and Western Medicine".

It is precisely because of the class identity of "poor and middle peasants" that barefoot doctors perfectly meet the requirements of "doctors that farmers can afford, use and stay". However, barefoot doctors are different from the image of village doctors or "witch doctors" in the past, and they are positioned and arranged in an institutionalized political atmosphere. Yang Nianqun believes that "under the dual discipline of institutional arrangement and human network, barefoot doctors will naturally strengthen their moral constraints."

In 1960s, malaria was prevalent in rural areas, but the villagers generally lacked common sense of epidemic prevention. Ma Wenfang can only send medicines from house to house for consultation and publicize malaria prevention knowledge. When people are not at home, they go to the fields to look for them. More than 360 households in the village run once a day for 7 days in a row. At that time, some villagers felt that they were in good health and were unwilling to take medicine. Barefoot doctors had to "send medicine to their hands, see the mouth, and not swallow it." After completing a course of medication, at intervals, they began to deliver medicines from house to house for two years until malaria was eliminated.

During the national patriotic health campaign, barefoot doctors, as the most basic executors of the health security system, also undertook the task of "two management and five reforms". Barefoot doctors should take care of water and feces, change wells, toilets, barns, stoves and the environment, and check from house to house whether they have been disinfected. As long as it is related to medical treatment, hygiene and health care, barefoot doctors have to do it, and there are endless things to do every day.

The article Barefoot Doctors and the Medical Pyramid published in the British Medical Journal in 1974 pointed out that as the bottom of the medical pyramid system, barefoot doctors’ semi-peasant and semi-doctor status determines that they can only provide basic and simple medical services and convey health concepts such as "washing hands before meals" to the public. They have played a great role in disease prevention, such as early diagnosis of esophageal cancer in Northeast China and nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Guangdong.

"As a product of a specific historical period, barefoot doctors and cooperative medical system are a creation of farmers in China under the condition of lack of health resources and serious unfair distribution." Li Decheng, an associate professor of Jiangxi Normal University, once wrote an article summarizing that barefoot doctors have built the bottom layer of the three-level medical prevention and health care network in rural areas, so that measures such as vaccination, vaccination and distribution of epidemic prevention drugs implemented by higher health administrative departments can be truly implemented.

After the disappearance of "barefoot doctor"

After 1976, with the end of the political movement, the number of primary health workers, including barefoot doctors, decreased at an average annual rate of 400,000.

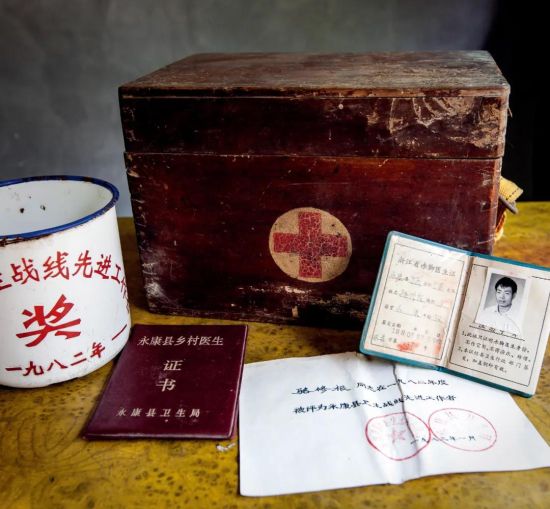

At that time, the health department began to standardize employees, control the number and quality of barefoot doctors, and eliminated a number of unqualified health personnel through examination and certification. The examination began in 1979. In 1981, the State Council approved the Report of the Ministry of Health on Reasonably Solving the Subsidy of Barefoot Doctors. It was mentioned in the document that "barefoot doctors who pass the examination and are equivalent to the technical secondary school level will be issued with a’ barefoot doctor’ certificate, and in principle they will be given treatment equivalent to the level of private teachers. For barefoot doctors who can’t reach the level of technical secondary school temporarily, it is necessary to strengthen training, and their remuneration, in addition to recording workers, should also be given appropriate subsidies according to local actual conditions. "

After the disintegration of the people’s commune, with the disintegration of the collective economic foundation, the rural cooperative medical system and the barefoot doctor system further lost their organizational support and economic support. By 1983, the number of barefoot doctors in China had dropped to more than 1.2 million.

On January 24th, 1985, Chen Minzhang, the former Minister of Health, pointed out in his speech at the National Conference of Health Directors that "the name’ barefoot doctor’ was put forward by Zhang Chunqiao and others in an article in the early days of the Cultural Revolution, and then it was widely used in various places. The meaning of this name is not exact either. Now we have decided not to use this name. In the future, anyone who has reached the level of a healer after examination is called a rural doctor; Those who fail to reach the level of healers are renamed as health workers. "

The next day, People’s Daily published the article "Stop using the name of" barefoot doctors "and consolidate the development of rural doctors", and the era of "barefoot doctors" ended here. Barefoot doctors retired and changed careers. Some left the public system to open clinics at home, while others contracted the original commune health centers, taking responsibility for their own profits and losses, and continued to practice medicine in the name of "barefoot doctors".

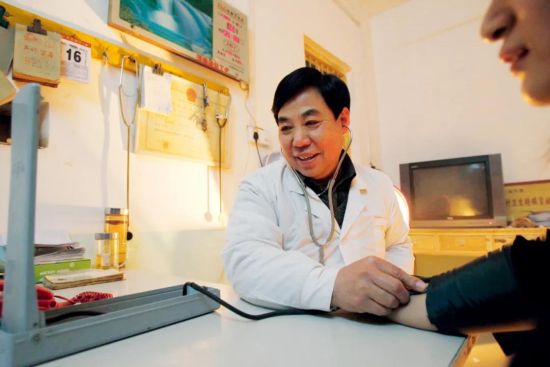

After the transformation, barefoot doctors have improved their professional level through retraining, further study and self-study. Coupled with the villagers’ original trust in barefoot doctors, village doctors were still very popular in the 1990s, when Ma Wenfang saw more than 150 patients a day. From "recording work points" to "self-financing", the village clinic still has a part of income. Ma Wenfang keeps enough income for his family to eat and drink, and the rest is fed back to the villagers to take medicines and give free vaccinations to children who can’t afford vaccines. In Ma Wenfang’s impression, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, rural doctors briefly experienced a "golden age".

Soon, by the mid-1990s, the eastern region developed rapidly, attracting a large number of farmers to go out to work. Village clinics have backward hardware, insufficient manpower and old doctors, which are in sharp contrast with big hospitals. With the increase of people’s income, villagers have gradually formed the consciousness of "going to big hospitals when they are sick". The survival of village doctors began to become difficult.

In fact, the transformation dilemma of rural primary health care system appeared after the collapse of the "barefoot doctor" system. Although the primary health workers in rural areas were still "barefoot doctors" in the past, they lost the original system guarantee and economic support and made a living in the market economy environment driven by interests. Obviously, they could no longer undertake the functions of epidemic prevention supervision of "barefoot doctors", and the rural primary health network could no longer operate effectively after entering the 1980s.

"The disintegration of the cooperative medical system and the transformation of the role of’ barefoot doctors’ have led to the plight of rural primary health care and the loss of basic medical security for farmers." Zhang Daqing said that in 2003, the China municipal government put forward the plan of establishing a new rural cooperative medical system and promulgated the Regulations on the Management of Rural Doctors’ Practice, so as to rebuild the rural primary health care service system. However, there are still many disharmonies between the new rural cooperative medical system and the medical services of rural doctors, and the service system that adapts to the medical consumption level and level of the new rural cooperative medical system needs to be improved.

"The current rural primary medical problems cannot be solved by simply restoring the original barefoot doctor system." Zhang Daqing pointed out that with the development of social economy, people’s demand for the quality of health care has also increased rapidly, and their awareness of health and financial investment in maintaining health have increased. It is understandable to pursue better medical services. The state can only guide graded diagnosis and treatment from the system design. More crucially, the system design of rural primary health service system should be clear about its functions and responsibilities.

After being elected as a deputy to the National People’s Congress in 2008, Ma Wenfang began to investigate the basic medical care in rural areas and the practice of village doctors. He visited more than 300 villages in 38 prefecture-level cities in 7 provinces including Henan, Shandong and Hunan, and found that the phenomenon of hollow villages is becoming more and more common, and the treatment of village doctors is low. Some villages even have no village doctors, and the level of basic health services in rural areas is worrying. "Grass-roots work needs specific people to do, and village doctors subsidize more than 1,000 pieces a month. Now in this era, who is willing to do it and who will take over in the future? What about basic medical care and public health in rural areas? " Ma Wenfang said with concern.